The collection, B Misc (Bethlehem Miscellaneous), has been the most challenging collection to catalog among the collections in Bethlehem and Winston-Salem. It includes early works transported from Germany and other works in Bethlehem that did not “fit” into a congregational or personal collections.

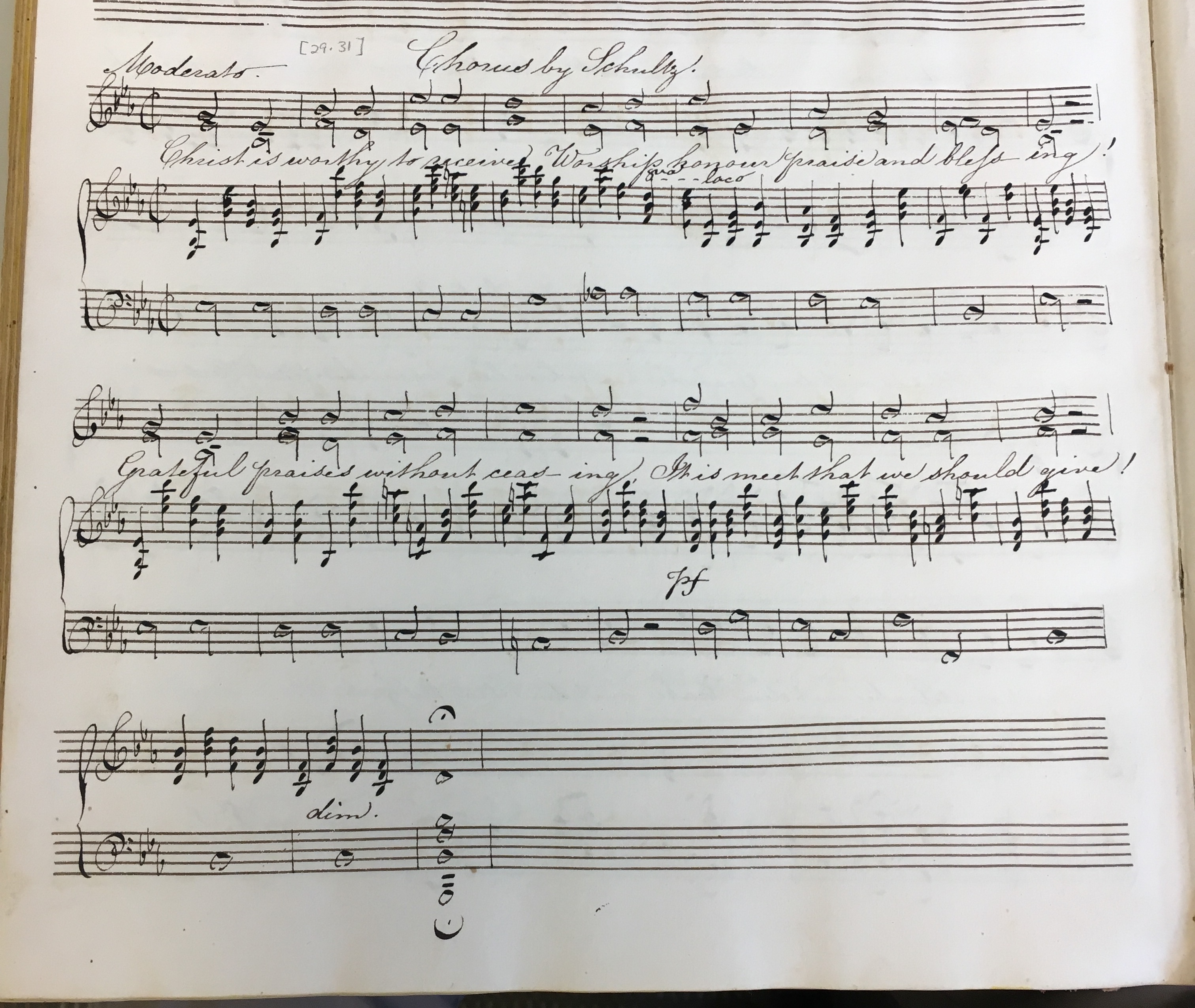

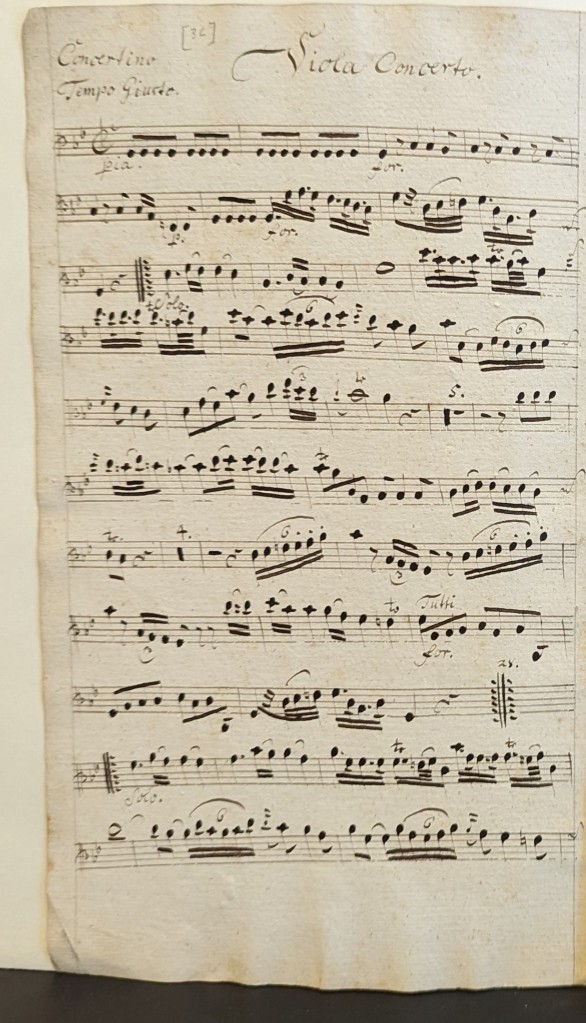

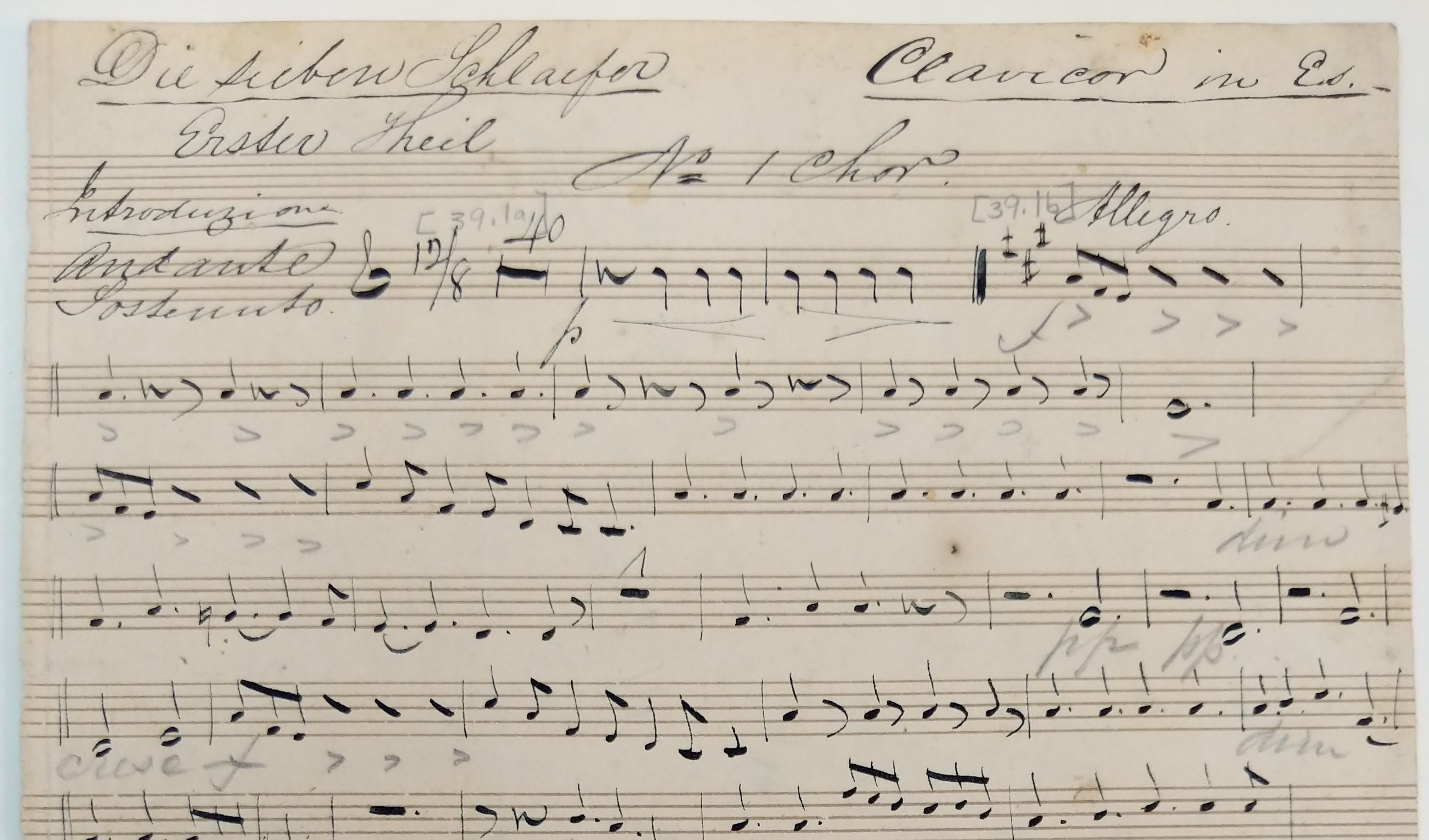

One of the most gratifying items I’ve worked on is the keyboard collection, B Misc [9]. It is identified as a “Collection of Cantatas and Arias by Schlicht, Molther, Eberhard, Gregor and Hasse”. It is a keyboard score, described as being in oblong format, 22 x 17.5 cm, 54 pages (numbered 233-296) ) and appears to have been extracted from a bound volume. [The numbered pages are the thread.] What was it part of?

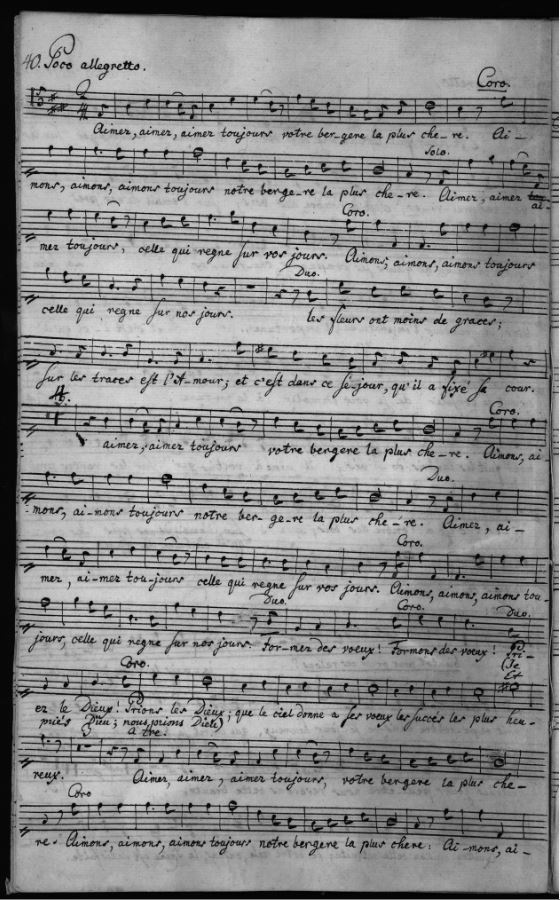

Going to the RISM catalog was the first stop, which revealed matching records for the same works in Herrnhut which originally belongs to the Collegium Musicum, Wetterau (a Moravian settlement in an area north of Frankfurt). In addition, the keyboard part, an essential element, was missing from each. I scoured the records in RISM and our records in OCLC to see if the keyboard in hand could be the keyboard part missing from among parts in Herrnhut. I surmised that B Misc [9] was the missing keyboard part, dating from between 1742 and 1747.

In March 2022, I wrote the following memo to the Archivists at the Herrnhut Archives, Caludia Mai and Olaf Nippe. Olaf responded that a member of the RISM group from the Saxonian State Library actually cataloged the works in Herrnhut. My colleague, Dave Blum, met Dr. Andrea Hartmann, who cataloged Herrnhut music manuscripts some twenty years ago. Her response follows after my memo.

Continue reading Following a thread…

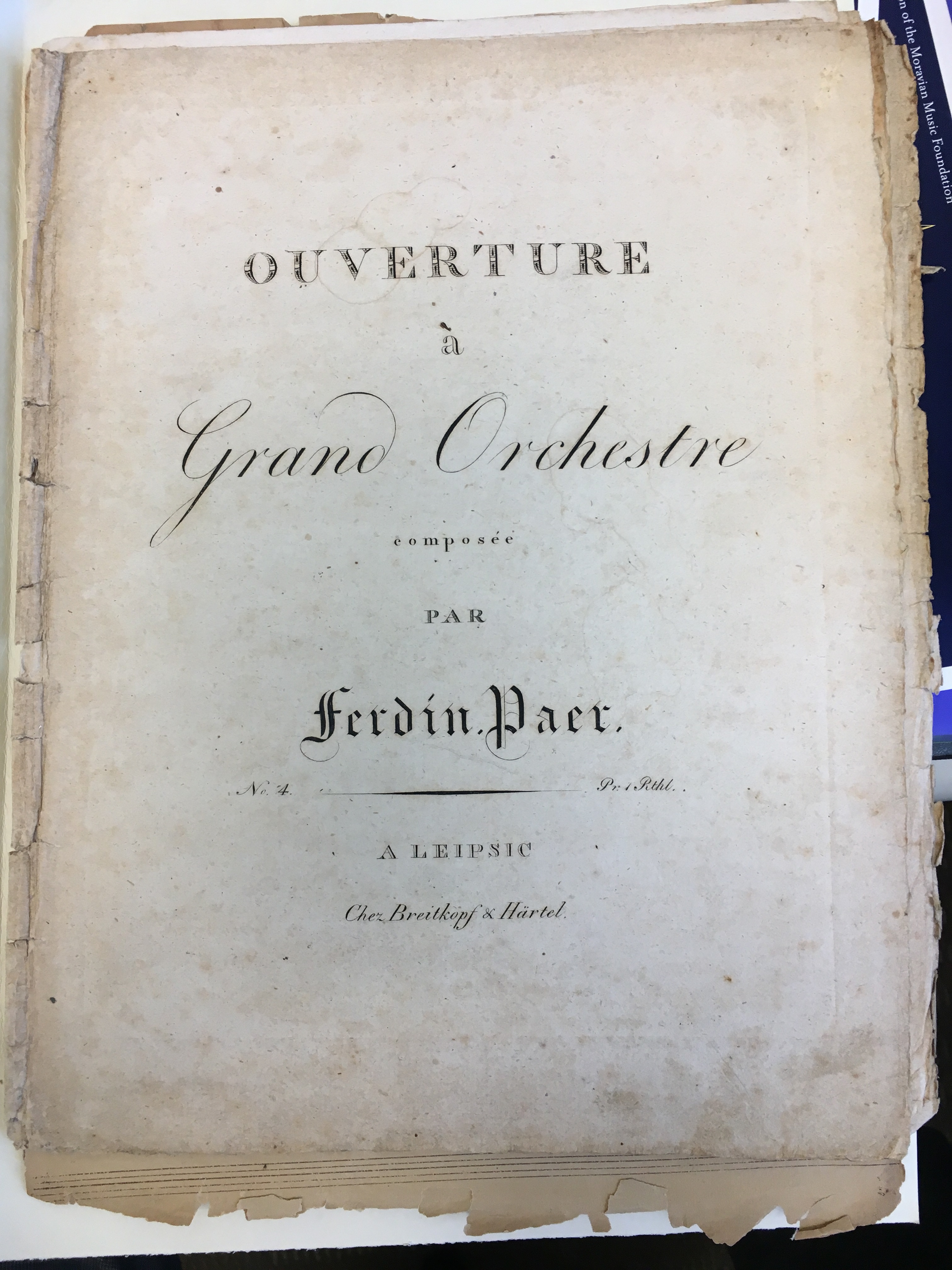

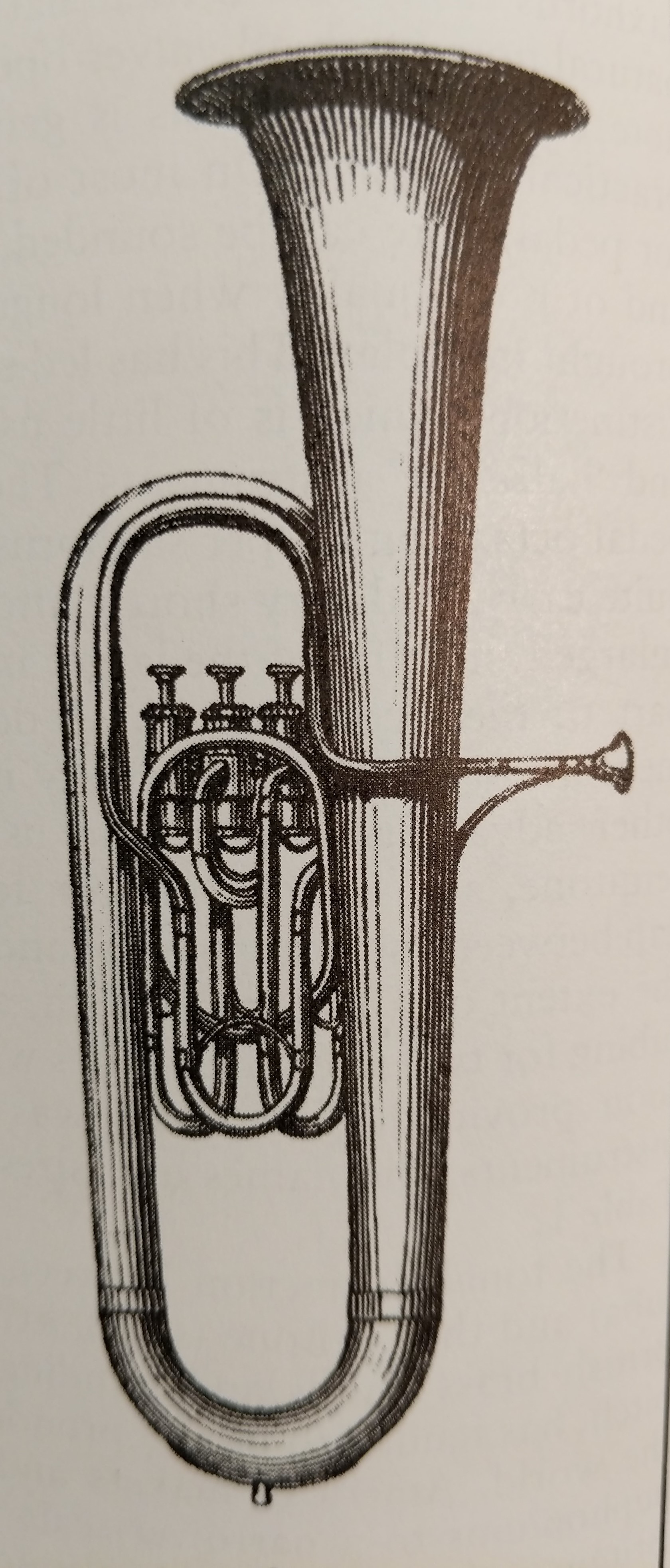

The bass sax horn, also invented by Adolphe Sax in the 1840s is likely an instrument that played with the Salem brass ensembles. In this case the bassoon II part was transposed for bass sax horn.

The bass sax horn, also invented by Adolphe Sax in the 1840s is likely an instrument that played with the Salem brass ensembles. In this case the bassoon II part was transposed for bass sax horn.

.

.